“Other researchers were skeptical about whether it is possible to make an accurate match between public records and individuals taking part in a life-long study, but New Zealand’s national databases are very reliable and Dunedin Study members have given us great information for matching over the years,” said Terrie Moffitt, the Nannerl O. Keohane University Professor in Duke’s departments of psychology & neuroscience and psychiatry & behavioral sciences. “We know every location they’ve lived, every name they’ve used. We’re able to match them with pretty much 100 percent accuracy back for many years.”

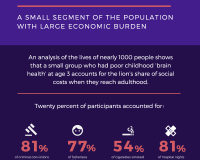

“The digitization of people’s lives allows us to quantify precisely how much a person costs society and which people are using multiple different costly health and social services,” Moffitt said. “Apparently, the same few clients use the courts, welfare benefits, disability services, children’s services, and the health-care system. These systems could be more joined up.”

The key information the researchers possessed was rich data about the study group in early childhood.

At age 3, each child in the study had participated in a 45-minute examination of neurological signs including intelligence, language and motor skills, and then the examiners also rated the children on factors such as frustration tolerance, restlessness and impulsivity. This yielded a summary index the researchers called “brain health.”

In the latest study, low scores on the brain health index at age 3 were found to predict high healthcare and social costs as an adult. “We can predict this quite well, beginning at age 3 by assessing a child’s history of disadvantage, and particularly their brain health,” Caspi said.

The findings remind Rena Subotnik, director of the Center for Psychology in Schools and Education for the American Psychological Association, of a recent effort in New Jersey to put a medical clinic in the neighborhood with the greatest need for services.

Educators might be able to do the same sort of thing for these young children at risk of higher social costs, she said. “These are all traits that can be controlled and improved upon with the proper interventions, so identifying them in young children is a gift,” she said. And all of society would benefit. “You get the best bang for the buck with early intervention,” Subotnik said.

Caspi and Moffitt stress that this ability to identify and predict a person’s life course from their childhood status should be an invitation to intervene, not discriminate.

“Any time you identify a population segment, the next thing people do is stigmatize,” Moffitt warned. But being able to predict which children will struggle is an opportunity to intervene in their lives very early to attempt to change their trajectories — “for everyone’s benefit,” Moffitt said. “This study really gives a pretty clear picture of what happens if you don’t intervene.”

“There is a really powerful connection from children’s early beginnings to where they end up,” Caspi said. “The purpose of this was not to use these data to complicate children’s lives any further. It’s to say these children — all children — need a lot of resources, and helping them could yield a remarkable return on investment when they grow up.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.